The New Normal for the Thai Economy

excerpt

A question that has increasingly concerned many of us is whether the mounting pressure of economic slowdown and other mostly unpleasant macroeconomic changes we are experiencing are cyclical or structural. Is it the legacy of the global financial crisis (GFC), i.e., the ongoing cyclical adjustment that follows a balance sheet recession? Or has the world reset itself because of several structural transformation that have long been underway independently of the GFC? This article discusses Thailand’s new normal, paying particular attention to what future growth and inflation will be.

There are two possible explanations for slow growth: a slowdown in trend growth or a persistently negative output gap. Consequently, a framework for thinking about an economy’s future growth can be organized in two ways: the long-run potential and the deviation from potential.

The most familiar notion of the new normal is the GDP trend that is projected to become flatter; from the supply-side perspective this could be a result of aging population, structural constraints affecting capital growth, and moderation in the rate of productivity gains as the economy has approached the technological frontier.

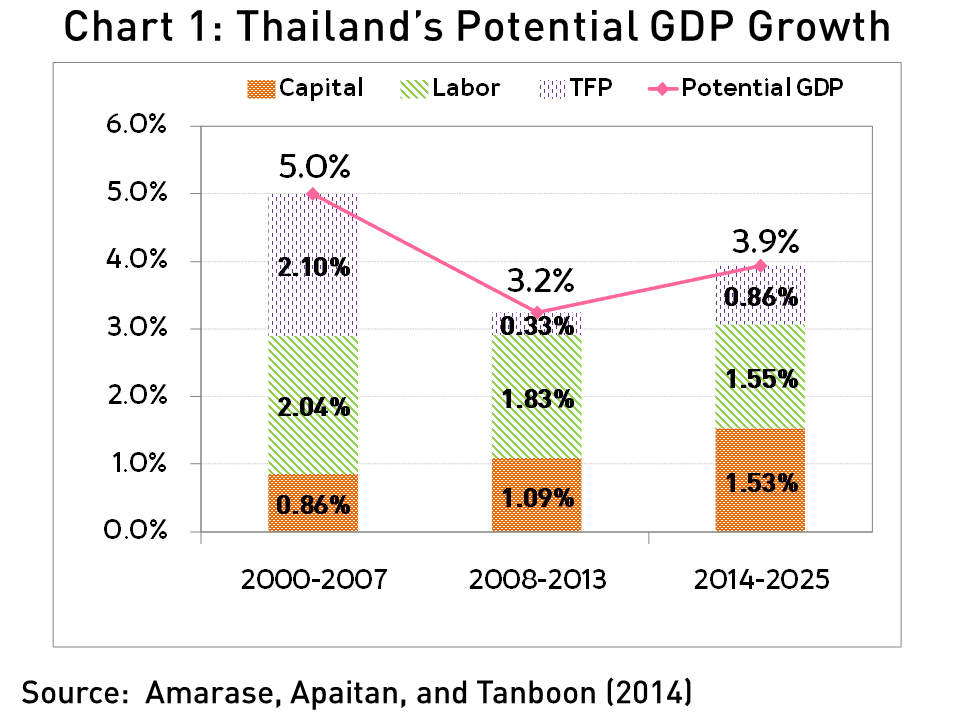

Chart 1 shows the sources of potential growth for Thailand over 2000–2025 estimated using the growth accounting approach (Amarase, Apaitan, and Tanboon, 2014). Prior to the GFC the acceleration in total factor productivity explains the bulk of the increase in trend output. This is consistent with the proliferation of global supply chains, technology spillovers that enabled the expansion of the production possibility frontier, and reallocation of factors of production to higher-productivity sectors. This development also happened in various emerging market economies (IMF, 2015).

Over the next 10 years, the positive contributions from both productivity and labor are estimated to be smaller relative to the pre-GFC period. Trend productivity will account for potential growth less due mostly to (1) the inadequacy of domestic R&D and (2) the moderation in technological spillovers following slower expansion in global value chains. Labor also contributes less due to aging population in line with declining birth rates and increasing longevity. Meanwhile, capital is expected to contribute more. Over the past decade Thai investment was restrained by successive negative shocks (notably, policy uncertainty caused by protracted domestic political instability). The adverse impacts of these shocks are expected to gradually dissipate going forward. In sum, Thailand’s potential growth is estimated to fall from 5 percent over 2000–2007 to around 4 percent over 2014–2025.

A number of economists have pondered a disturbing possibility that the recently observed low growth is characterized by a persistent aggregate-demand shortage (as opposed to lower potential growth described above). Prolonged reluctance of consumers to spend and businesses to invest leaves the output gap persistently open.

This notion of “secular stagnation” has the origin in a question by Alvin Hansen, an American economist, about 80 years ago. The question was whether there would be sufficient investment demand to sustain future economic growth given excess capacity and the lack of good investment opportunities at the end of the Great Depression. With investment deficit and hence excess savings, there would be a persistent decline in the economy’s equilibrium real rate of return, which is an important characterization of secular stagnation. Today, Summers (2013) sees limited investment and the slow overall growth in the U.S. as relevant for the new normal of secular stagnation.1

Many economists are skeptical of secular stagnation. Bernanke (2015) argues that the availability of profitable investment opportunities elsewhere in the world should reduce the likelihood of secular stagnation. If domestic households and firms turn to investment overseas, the resulting financial outflows would be expected to weaken the exchange rate, which in turn would promote exports. Increased exports would raise production and employment at home, helping the economy to reach full employment. Moreover, it is questionable that the economy’s equilibrium real rate of return (also known as the natural rate of interest) can really be negative for an extended period, as some of the forces that drive the real interest rate trend down during the recent years are slowly fading.

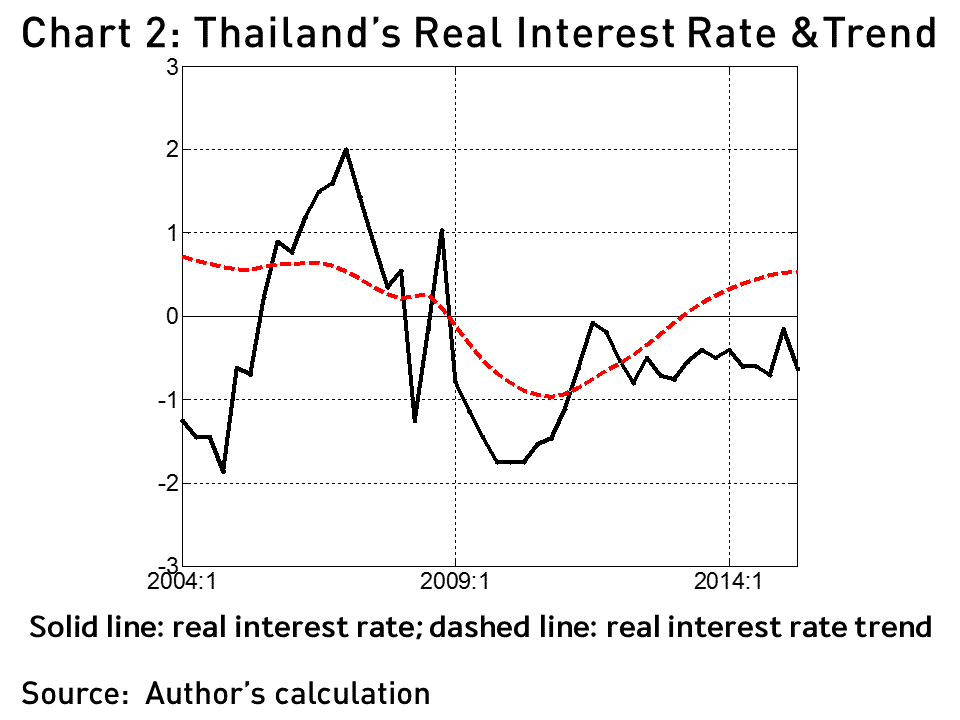

What are the evidence that might possibly dispute secular stagnation for Thailand? Chart 2, obtained using the Kalman filter à la Laubach and Williams (2003), shows the real policy interest rate (solid, in black) and the estimated natural rate of interest (dashed, in red) — the latter is defined as the real interest rate consistent with output converging to potential and inflation converging to the target. Prior to the GFC the natural interest rate fluctuated around 0.5 percent, dipped below zero in the aftermath of the GFC, and thereafter gradually returned to a positive level. This finding is in accordance with Bernanke’s (2015) conjecture that the natural rate of interest is unlikely to be persistently negative.

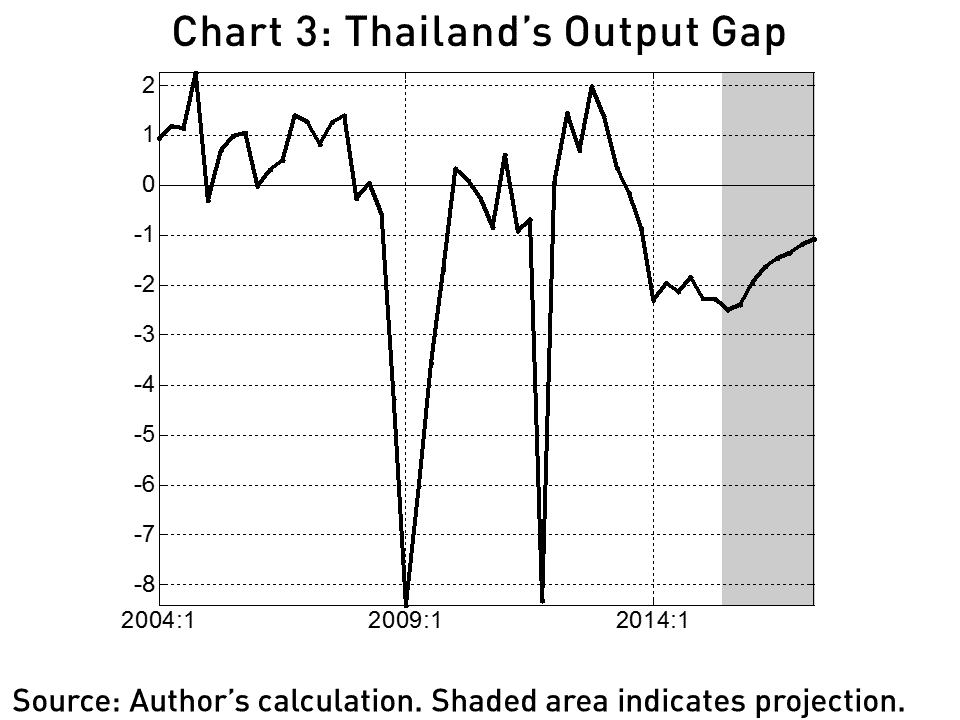

In addition, Thailand’s output gap is expected to gradually return to zero as shown in chart 3. A recovery in external demand, together with an exchange rate that has recently been weaker than previously, and a pickup in domestic demand prompted by several recent fiscal stimulus measures which should induce private investment to some extent going forward should help minimize the possibility of secular stagnation for Thailand.

Analogous to the analysis of future growth by examining long-run potential and the deviation from potential, here the analysis of future inflation will be conducted by examining trend inflation and inflation dynamics around the trend.

Trend inflation has declined over the long term thanks partly to increased anchoring of expectations by credible monetary policy. Theoretically trend inflation is ultimately determined by where long-run inflation expectations have settled, and empirical evidence supports the notion that monetary policy is responsible for inflation expectations. For the U.S., Yellen (2015) illustrates that only when the Fed started to commit to maintaining inflation at a low and stable level in the late 1970s did inflation trend lower; from the late 1990s onward, trend inflation has stabilized around 2 percent despite the GFC and the recent developments in the oil market.

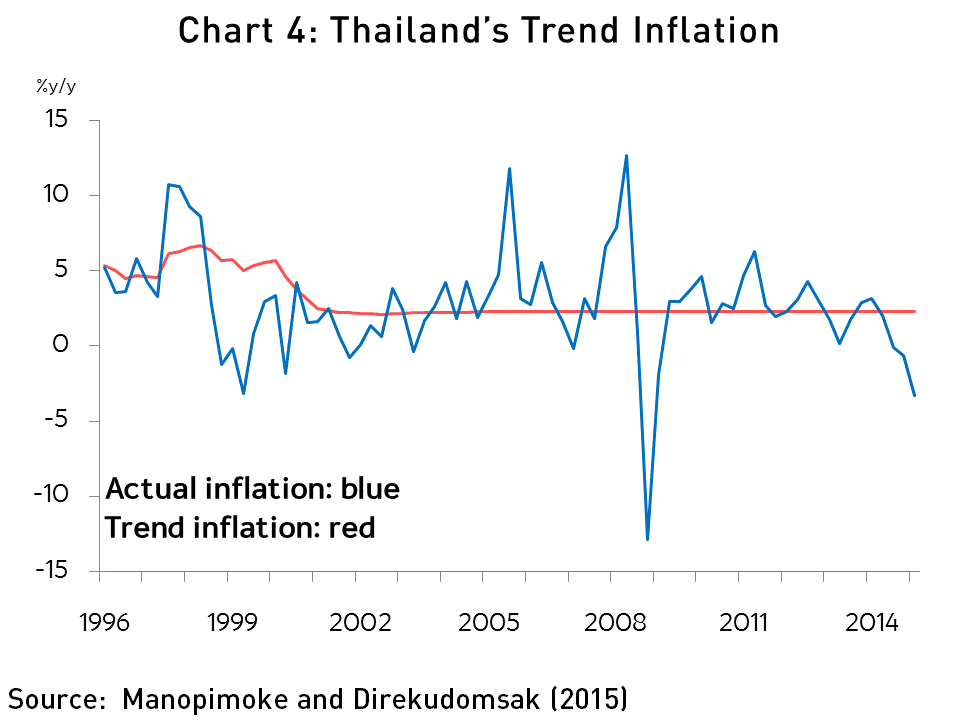

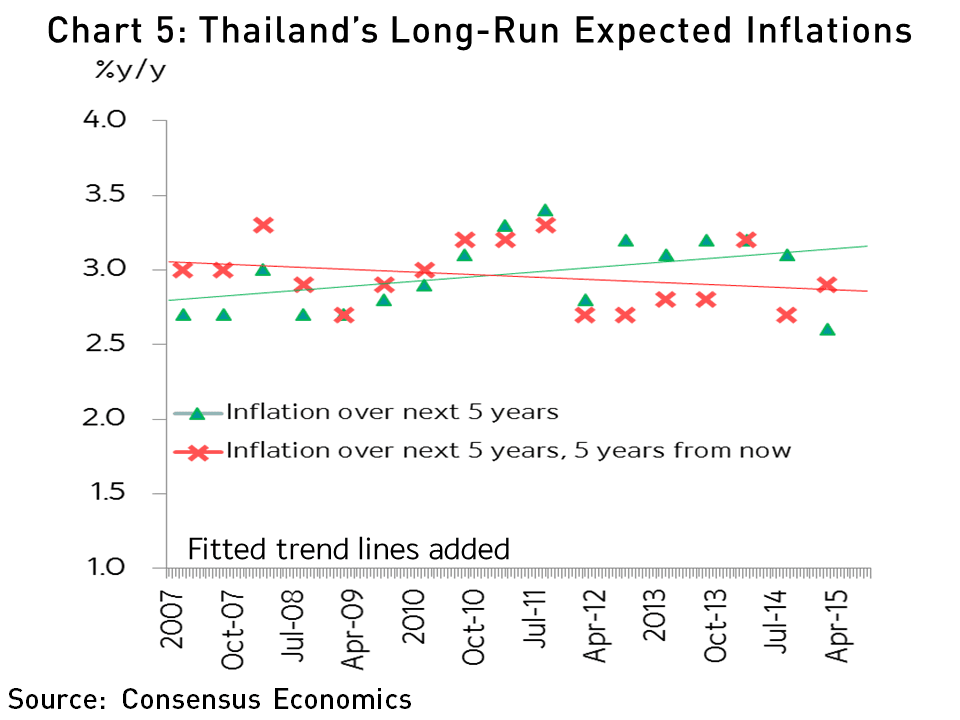

For Thailand, Manopimoke and Direkudomsak (2015) estimate an unobserved component model for the New Keynesian Phillips curve using data between 1993 and early 2015. One finding, shown in chart 4 which is analogous to the U.S. counterpart, is that trend inflation was not well anchored during 1996–2000 — before a credible monetary policy framework was in place. However, after the adoption of inflation targeting in 2000, trend inflation is found to be anchored. This stability of the estimated trend inflation is confirmed by the overall stability of long-term inflation expectations obtained from a survey shown in chart 5. The key point is that stability of trend inflation continues to the present days, and based on the latest information there is no sign that trend inflation has recently been shifted down. In other words, there is no new normal for trend inflation.

The Phillips curve posits that short-run inflation dynamics depends on, among other things, the cyclical balance in the economy between aggregate demand and potential supply. However, we witness that inflation has become less sensitive to the output gap. Even in an extreme episode such as during the recent GFC, with a massive opening of the output gap, sharp disinflation was absent. This gives rise to the notion that the Phillips curve no longer well characterizes inflation dynamics in the new normal.

Consider the case of missing disinflation during the GFC. Theoretically, as firms still operate below their full capacity, when demand is gradually stimulated, they will start producing more without incentives to raise prices yet; firms will increase prices only when demand gets sufficiently large that it approaches their capacity constraint. On the other hand, during boom times, a small amount of additional demand will translate into strong price increases. In other words, the Phillips curve could be almost flat when the output gap is very negative, approximately linear when the output gap is in the neighborhood of zero, and becomes convex when output considerably exceeds potential output.

Refining the empirical Phillips curve with time varying parameters indeed explains missing disinflation during GFC. For instance, Constâncio (2015) illustrates for the euro area that, once the parameters are allowed to change over time, the Phillips curve remains an important vehicle at the ECB to discuss inflation dynamics. Using these time-varying parameters instead of constant parameters not only accounts for the missing disinflation during the GFC but also improves the fit of the Phillips curve during the prolonged period of low inflation after 2012 in the euro area.

An alternative to using time-varying parameters is to incorporate regime switching, Manopimoke and Direkudomsak (2015) allow shifts in a number of parameters in the Phillips curve — among others, the variances in the temporary and persistent components of Thai inflation and the tightness of the links between inflation and the output gap for Thailand. The authors also add various external variables, such as the global output gap, the terms of trade, import prices, oil and nonoil commodity prices, and the real exchange rate.

Important findings are that (1) inflation has become less sensitive to the domestic output gap; (2) the effects on Thai inflation of external factors such as oil prices have increasingly mattered and mattered more relative to nonoil commodity prices; (3) the role of the global output gap, which includes the effects of trade globalization on prices, has recently declined in line with diminished participation in the global value chains. These insightful findings, obtained from modified and augmented versions, indeed affirm the usefulness of the Phillips curve in capturing those new normal aspects of short-run inflation dynamics in Thailand.

Structural changes in the global and domestic contexts have ushered the Thai economy into a new normal in several aspects. Although potential growth is expected to be lower, Thailand can shift itself to a better new normal with appropriate supply-side policies, with the assistance of attentive monetary policy in closing any output gap in the short run. In terms of inflation, while short-run inflation dynamics have undergone several changes, a credible monetary policy framework and a demonstrated commitment to fulfill a monetary policy target will work to anchor long-term inflation expectations, thereby facilitating an eventual return of inflation to its target. Therefore, monetary policy has a part to play in navigating the challenges of the new normal. Yet, as El-Erian (2010) mentioned, structural challenges require structural responses, and it is incumbent on both the public and private sectors to respond with the timely and efficient structural transformation in order to move to a better new normal.

Amarase, N., T. Apaitan, and S. Tanboon (2014), “Potential Output Estimation.” Presentation at the Bank of Thailand Workshop on Potential Output Estimation, Bank of Thailand.

Bernanke, B. (2015), “Why Are Interest Rates So Low.” Ben Bernanke’s Blog, Brookings Institution.

Constâncio, V. (2015), “Understanding Inflation Dynamics and Monetary Policy.” Panel remarks at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

El-Erian, M. (2010), “Navigating the New Normal in Industrial Countries.” Per Jacobsson Foundation Lecture, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

International Monetary Fund (2015), “Where Are We Headed? Perspectives on Potential Output.” Chapter 3 World Economic Outlook, April, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

Laubach, T., and J. Williams (2003), “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 83, 218–231.

Manopimoke, P., and W. Direkudomsak (2015), “Thai Inflation Dynamics in a Globalized Economy.” Paper presented at the Bank of Thailand Economic Symposium.

Summers, L. (2013), “IMF Economic Forum: Policy Responses to Crises.” Speech at the IMF Fourteenth Annual Research Conference, Washington, D.C.

Yellen, J. (2015), “Inflation Dynamics and Monetary Policy.” Remarks at the Philip Gamble Memorial Lecture, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

- Why is secular stagnation important? In this case it is difficult to achieve full employment, low inflation, and financial stability at the same time. As secular stagnation entails chronic demand deficit and excessive savings, the natural rate of interest will decline to a persistently low level — possibly negative. To stimulate the economy, the real interest rate would have to be driven lower than that negative natural rate of interest. However, the most negative the real rate can be is zero (the lower bound on the nominal interest rate) minus expected inflation. Consequently, the central bank cannot achieve full employment unless it either (1) raises its inflation target or (2) accepts the recurrence of financial bubbles as a means of increasing spending. It is in this sense that with secular stagnation the trinity of full employment, low inflation, and financial stability appears difficult to achieve simultaneously — a disturbing possibility.↩