The Effects of the 300 Baht Minimum Wage Policy

excerpt

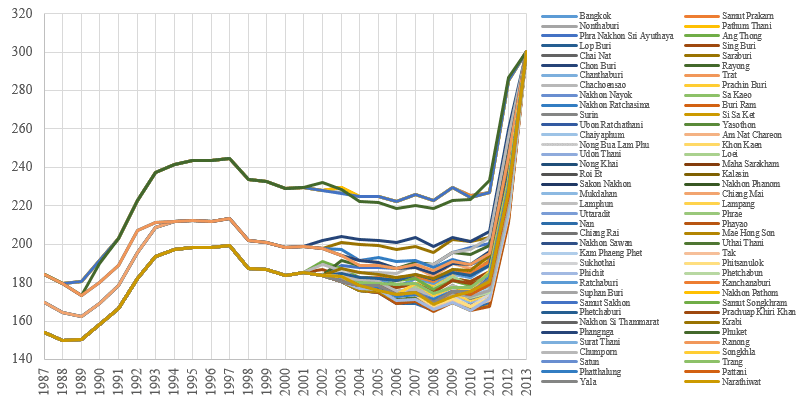

This article investigates the employment and distributional effects of changes in the minimum wage in Thailand over the 1998–2013 period, paying particular attention to the most recent policy change which led to the implementation of a uniform national statutory minimum wage of 300 Baht per day in January 2013. The new policy, announced by the government in 2011, was a far cry from the former system where minimum wages were set provincially, depending on the cost of living and the economic climate of each province.1 The magnitude of the hike was also unprecedented, rising on average by around 60 percent2 in real terms from March 2012 to January 2013. In this brief, we give an initial account of the responsiveness of the Thai labor market to the policy change.

Lathapipat (2016) and Lathapipat and Poggi (2016) start by assessing the causal impacts of the minimum wage on the average real hourly wage and various employment outcomes of all working age population (15 to 64 years old), as well as of selected population subgroups (post-secondary educated, 15–24 year-old secondary or less-educated, and 25–64 year-old secondary or less-educated) who have already completed formal schooling at the time of survey. Our dependent variables are respectively: the natural logarithms of real hourly wage and weekly working hours, a dummy variable for employment that takes on the value of one if the individual is working, and dummies for employment by production sector (agriculture, industries, and services) and work status (employee of micro/small &medium/large size private sector firm3, self-employed worker, unpaid family worker, and employee of public & state-owned enterprise). In order to distinguish between short- and long-run4 effects of the minimum wage change and to detect any anticipation effects, we employ a dynamic model with distributed leads and lags in log real minimum wage. The chosen specification covers a 10-quarter window, starting at four quarters before the change in the minimum wage and continuing to six quarters after the change.

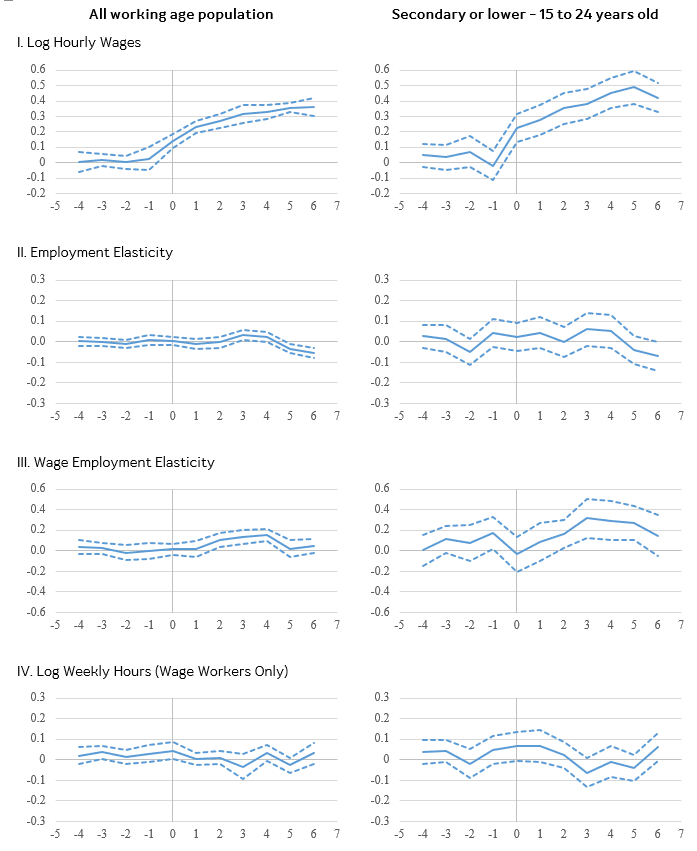

The estimated time paths of the minimum wage elasticity of hourly wages, employment, and weekly working hours are reported in Figure 2. The left-hand column presents the results for all working age population, while the right-hand column shows the results for 15–24 year-old secondary or less-educated population subgroup (15–24 year-old low-skilled from hereon). Both hourly wage elasticity graphs in panel I of Figure 2 clearly show that on average, for any type of wage earner, less than half of the wage adjustment occurred at policy implementation. The full effects are observed around 5 or 6 quarters thereafter. Unsurprisingly, the wages of young low-skilled workers were more affected than those of the average worker, with maximum estimated elasticity of 0.4885 (5 quarters after the minimum wage change) compared to 0.361 (6 quarters after) for the average worker.

Turning now to the employment effects, panel II of Figure 2 shows that the employment elasticity throughout much of the time horizon are indistinguish-able from zero for both the working age population and for the subgroup of 15–24 year-old low-skilled workers. The long-run effects (6 quarters after the minimum wage increase), however, are slightly negative and significant for the two population groups, with employment elasticity of -0.054 and -0.071 respectively.

The time paths for weekly working hours (for wage workers only) are presented in panel IV of Figure 2. They show positive and significant contemporaneous increase in weekly working hours for both population groups of interest. Nevertheless, the long-run elasticity for all wage workers is not significantly different from zero at conventional levels, while the corresponding elasticity for the 15–24 year-old low-skilled wage workers is a significant positive 0.064.

It should be mentioned that the distinction between wage and non-wage employment is very important in the context of Thailand, whose economy consists of a large informal sector which is partly represented by non-wage occupations. It can be inferred from panels II and III of Figure 2 that the increase in the minimum wage has brought more workers out of informality and into formal sector employment. This can be seen from the significant negative long-run employment elasticity for both population groups and the positive time paths of wage employment elasticity throughout the entire 6-quarter window after the increase in the minimum wage.6

Our discussion thus far has focused primarily on real hourly wage, employment, and weekly working hours elasticity. This is because estimates of the magnitudes of these particular elasticity contain important information needed to calculate the net benefits of a minimum wage policy. Whether the net benefit is positive or negative for a population group of interest can be measured by the change in the total wage bill paid to the population group. This in turn depends upon whether the sum of the estimated real hourly wage, employment, and weekly working hours elasticity is positive or negative.

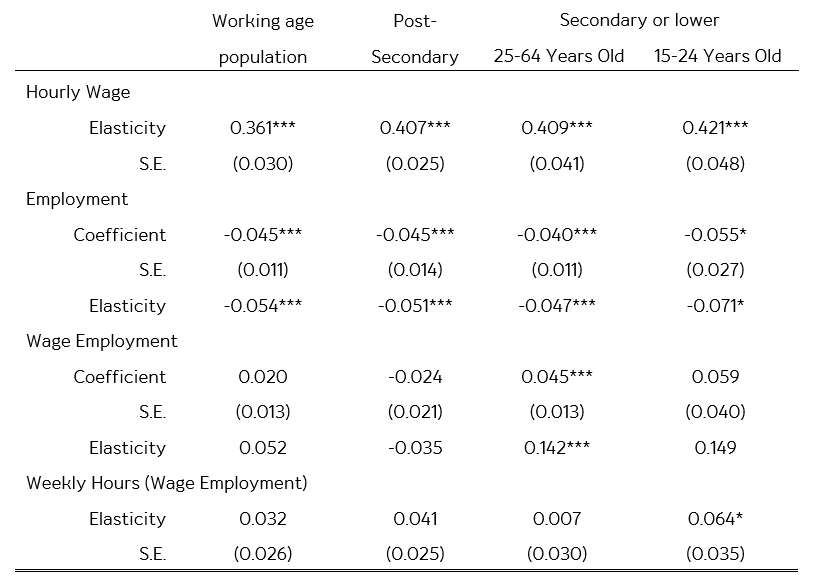

In order to simplify presentation, we summarize in Table 1 the estimated long-run effects of minimum wage change on the key variables needed to determine the net benefits of the minimum wage policy. Also included in the Table are long-run coefficient and elasticity estimates of the variables for two other population subgroups we have not focused on. These are the post-secondary- and 25–64 year-old secondary or less-educated groups. As can be inferred from all four columns in Table 1, the net benefits of the minimum wage policy are clearly positive for the entire working age population, as well as for all of the population subgroups considered in this study (whether aggregate employment or wage employment elasticity are used in the net benefit calculations). We therefore conclude from these evidences that the overall welfare of workers have improved due to the recent change in the minimum wage policy.

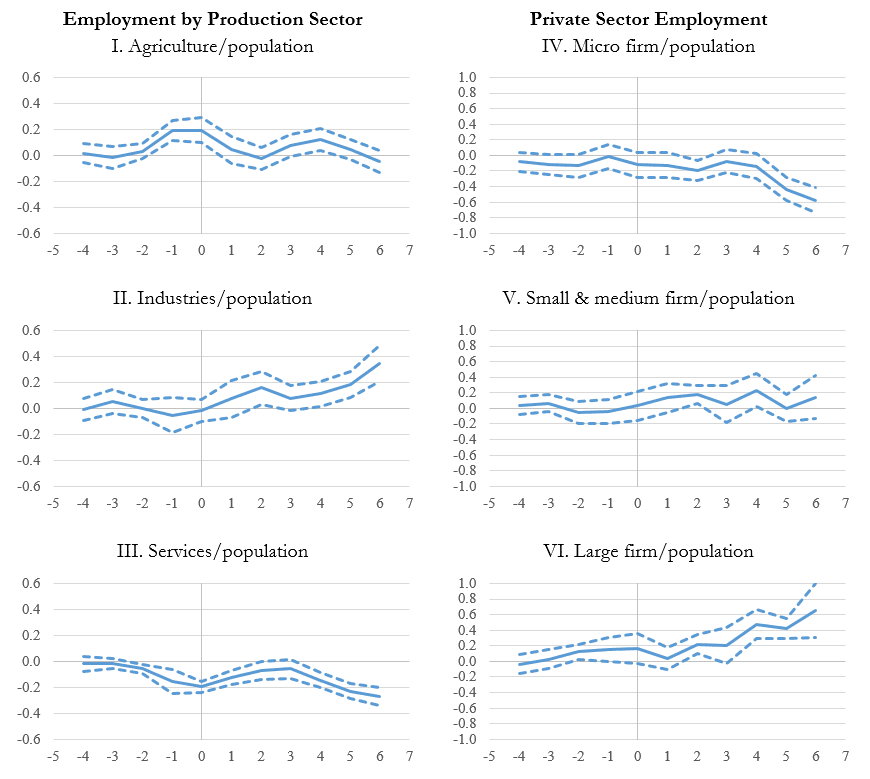

The time paths of minimum wage elasticity of employment for the entire working age population in the three broadly-defined production sectors, namely, agriculture, industries, and services, are reported in the left-hand column of Figure 3. We can see from panel III of Figure 3 that the employment share in services had already started to decline two quarters prior to the increase in the minimum wage. This is not surprising given the fact that the policy had been widely anticipated. Further and more substantial fall in services employment followed at the time of policy implementation. From panel I of Figure 3, we can see a near mirror image rise in agricultural employment, while no significant change in aggregate employment can be detected (see panel II of Figure 2). These graphs therefore provide clear evidence that the Thai labor market is very flexible in absorbing short-run shocks to the economy through the shifting of labor between non-agricultural and agricultural activities.

Six quarters after the minimum wage increase, however, we observe a large contraction in services employment share, with an estimated long-run response of -0.271. Furthermore, we find no significant long-run impact on agricultural employment. However, from panel II of Figure 3 we can see a large and significant increase in industries sector employment share (elasticity of 0.349), but the long-run expansion of employment in industries has not been sufficient to absorb all of the displaced services sector workers. As a result, a small decline in aggregate employment can be detected 6 quarters after the increase in the minimum wage (see panel II of Figure 2).

In the right-hand column of Figure 3, we divide private sector employees into three distinct groups in accordance with the size of the firms they were working in. The three groups are: micro enterprises, small & medium-, and large-sized private sector firms as defined previously. Immediately striking is the observation that the share of employment in micro enterprises started to decline sharply one year after the increase in the minimum wage, with an estimated long-run elasticity of -0.576. At the opposite end of the spectrum, we can see an equally remarkable rise in large firm employment share six quarters after the increase in the minimum wage. We do not, however, detect any significant change in the employment share of small & medium sized private sector firms over the period. At the aggregate level, the private sector employment-to-population ratio has remained stable in the long-run. These evidences unambiguously suggest that micro enterprises were more disproportionately hurt by the steep increase in the labor cost. Furthermore, the observed employment expansion of large private industrial sector firms in response to the rise in the minimum wage could indicate a presence of labor market imperfections, where these large firms possessed some degree of monopsony power.

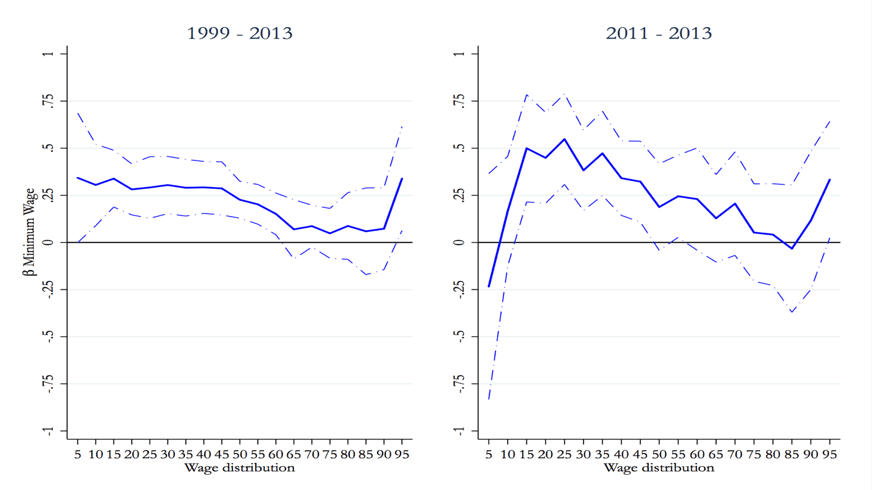

In this part of the study, we investigate the impact of the minimum wage policy across the entire wage distribution for private sector employees, using a Recentered Influence Function (RIF) regression applied to a panel of provincial wage distributions. The results, summarized in Figure 4, show that the minimum wage has had a positive impact for those at the lower end of the wage distribution, with evidence of positive spillovers beyond.

During the entirety of the period of analysis (1999-2013), covering the period of provincial minima followed by a national statutory minimum, the increase in the minimum wage can be seen to have a positive impact on the wage distribution up to the 60th percentile. On average, an increase in the minimum wage of 10 percent is associated with an increase of around 3 percent in the average hourly wage of workers ranked below the median. The effect appears to be stronger in the 10th and 15th percentiles (and weakly significant, but positively affecting the lowest 5th percentile). The effect decreases as it reaches the median and becomes indistinguishable from zero beyond the 60th percentile.

For the latest policy change (2011–2013) which led to the introduction of the statutory minimum wage, while having no effect at the very bottom of the distribution, had a strong positive impact beginning at the 15th percentile, and the impact progressively declines approaching the 45th percentile. In between the 15th and 25th percentiles, an increase in the minimum wage of 10 percent is associated with an increase in the mean wage of around 5 percent within the percentile range. The effect extends until the 45th percentile, with positive effects of around 3 to 4 percent. Overall, the evidence suggests that the minimum wage has had a positive effect on those at the lower end of the wage distribution. However, it has not translated into higher wages for those at the very bottom of the distribution as non-compliance may have kept these very low-paid workers at below-minimum.

This article investigates the impacts of changes in the minimum wage level in Thailand with a focus on the latest policy shift from provincial minima to a single national minimum wage of 300 Baht per day. We focus on the temporal effects of the policy, evaluated for employment, hourly wage rate, and weekly working hours. Additionally, we propose an analysis of the net benefits of the policy and of the distributional effects it induced.

We find aggregate employment to be rather stable with some minor downward adjustments six quarters after the policy introduction for all types of workers, with no contraction in weekly working hours. Similarly, for young low-skilled workers we find no immediate unemployment effect, but some marginal reduction six quarters afterwards and some increase in hours worked.

In terms of employment by occupation type, we find movement out of non-wage work and positive increase in employment in wage occupations. In the private sector, significant long-run reduction of employment in micro-enterprises happened hand-in-hand with greater employment in large industrial firms, and no significant effect on small & medium enterprises can be detected. In terms of wage analysis, we find positive effects of the minimum wage on the hourly wage distribution, with effects spanning up to the 60th percentile, but with no effect on the lowest percentile.

Our findings can be reconciled with a scenario of imperfect labor markets, where firms act with some degree of monopsony power. Once a higher minimum is introduced, the effects on aggregate employment are minimally damaging because some firms are able to comply, while worker redistribution across firms may apply and there are sizeable positive effects on the wage distribution.

Hence, the application of a higher minimum entails some gains and losses. As suggested by our findings, gains arise for wage workers, who can now obtain a higher reward for their labor after a prolonged period of stagnation in real wages, and also for firms, which can find a bigger pool of candidates available for work. However, losses may apply to firms and wage workers too. Some firms, especially the micro enterprises, could be forced out of the formal sector or out of the market altogether as they cannot compete for workers with larger monopsonistic firms. Furthermore, these large firms could temporarily see their profits reduced to adjust to the higher minimum. Workers could be penalized too if the bargaining power of some, namely the very low-paid, is reduced due to increases in non-compliance.

Although we are able to show some evidence for the early stages of the policy, this article is suggestive of the need for consistent and gradual minimum wage adjustments, which we find to be useful in reviving the wage distribution without depressing employment, while avoiding excessive profit losses on one side and unnecessary close-down or regression into informality on the other. Future adjustments of the minimum wage should be set at a prudent level, with simple guidelines for employers on compliance and enforcement activities.

Lathapipat, D. (2016): “Assessing the effects of the minimum wage on wage inequality: An extension of the Unconditional Quantile Regression to a Provincial Panel.” PIER Discussion Paper (forthcoming)

Lathapipat, D. and C. Poggi (2016): “From Many to One: Minimum Wage Effects in Thailand.” PIER Discussion Paper (forthcoming).

- Since April 2012 a daily minimum wage of 300 Baht was applied in seven pilot provinces (Bangkok and vicinities plus Phuket province), while an increase of approximately 40 percent was applied to the minima in the remaining provinces. The policy lasted for nine months and was followed by the introduction in January 2013 of a statutory minimum of 300 Baht per day for the whole kingdom.↩

- Weighted average real minimum wage, where the weights are the total working hours of all workers in the country.↩

- Private sector firms account for around 37 percent of total employment (excluding employers) over the 1998–2013 period. Micro enterprises is defined as those with 10 persons or less, small & medium size firms employ between 11 and 100 people, while large firms employ more than 100 people.↩

- Due to the limited length of time that we have to observe the labor market impacts from the recent change in the minimum wage policy, we will refer to the “long-run” effects of the policy as the labor market effects observed 6 quarters (or one and a half years) after the increase in the minimum wage.↩

- The estimated elasticity of 0.488 can be interpreted as follows: a 10 percent increase in the real minimum wage is associated with an increase in the average real hourly wage of 4.88 percent for this particular group of workers.↩

- However, the positive minimum wage elasticity of wage employment for both population groups are not statistically significant in the long-run.↩