Does money make people right-wing and inegalitarian?

excerpt

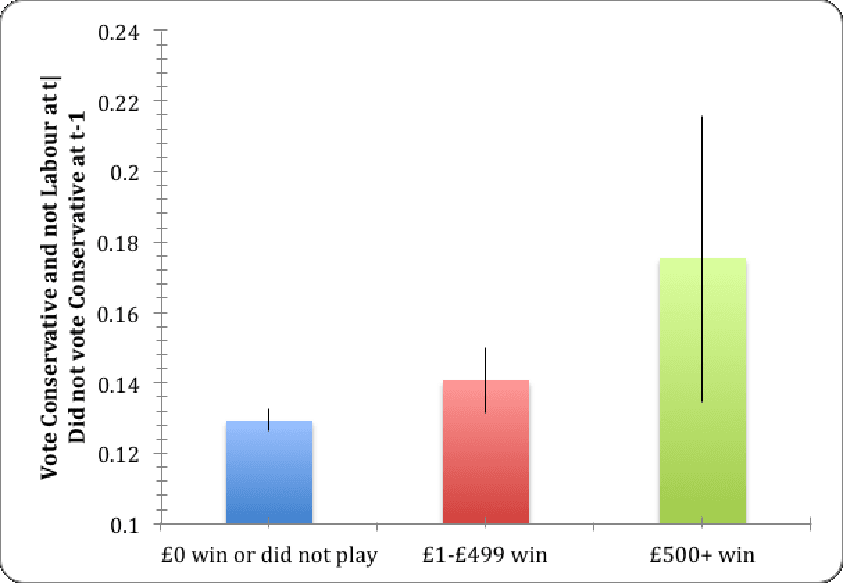

The underlying causes of people’s political attitudes, and of their preferences for or against redistribution, are imperfectly understood. This study exploits a natural experiment offered by the British national lottery. Comparing people before and after lottery windfalls, it shows that winners switch towards support for a right-wing political party, and are less egalitarian. The larger the win, the more individuals tilt rightwards. Small wins have no effect.

Voting is the foundation of modern democracy. Yet the causal roots of people’s political preferences are imperfectly understood. One possibility is that individuals’ attitudes to politics and redistribution are motivated by deeply ethical views. Another possibility — perhaps the archetypal economist’s presumption — is that voting choices are made out of self-interest and then come to be embroidered in the mind with a form of moral rhetoric. Testing between these two alternative theories is important intellectually. It is also inherently difficult.

Our study proposes a new form of test. It provides longitudinal evidence consistent with the second, and some might argue more jaundiced, view of human beings. The paper exploits a panel data set from Great Britain in which people’s political attitudes are recorded annually. In the data set, some individuals serendipitously receive lottery windfalls from the popular and widely-played weekly National Lottery. The paper shows that the larger is a person’s lottery win, the greater is that person’s subsequent tendency (in the data range of wins between 500 pounds sterling and 180,000 pounds sterling), after controlling for other influences, to switch their political views from left to right. Small wins, however, have no discernible effect. There is also evidence that lottery winners are more sympathetic to the belief that ordinary people ‘already get a fair share of society’s wealth’.

As an introductory aid to thinking, it is possible to consider a simple model in which it is rational for different kinds of people to vote different ways. The framework has an economic flavor. Intuitively, what happens behind the formal analytic is that, because by assumption,

(i) some individuals have higher income

(ii) some people derive greater utility (or happiness) from public goods like a national health system and community safety that are funded out of tax revenue

it is possible to see analytically the likely relationships between income and political views. So imagine a world in which individual earn real income Y and there is an amount of public good P. Imagine also that a rightwing government is one that provides a relatively small amount of the public good but demands a relatively low tax rate on income to fund it (it is useful to think of the Conservatives party in the UK and the Republican party in the US here), and a leftwing government is one that provides a relatively large amount of the public good and funds this with a relatively high tax rate on income (i.e. the Labour party in the UK and the Democrats in the US).

From these assumptions, it is easy to see that as people’s income goes up, their marginal disutility from a relatively higher tax rate on income will also go up and their marginal utility from public good will go down. What this implies is that as people becomes richer, their political preference will naturally shift from a leftwing government toward a rightwing government. They will also more likely to become less egalitarian – i.e. against redistributive policy – in the process.

The data source used in the analysis is the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). This is a nationally representative random sample of households, containing over 25,000 unique adult individuals, conducted between September and Christmas of each year from 1991. Data on lottery wins were collected for the first time since 1997 (Wave 7). Our focus will be only on lottery winners at the year of winning.

Our two outcomes of interest are (i) the extent of people’s support for either the Labour (leftwing) or the Conservative (rightwing) party, and (ii) people’s attitudes towards redistribution.

Our preliminary analysis reveals that lottery winners who win a relatively large amount (500 pounds or above) are significantly more likely to switch their voting preference from a leftwing party in year t to a rightwing party in year t+1 compared to winning small (1–499 pounds). In a regression that controls for own individual income and many other relevant personal characteristics, we find that a 1% increase in lottery win increases the probability of an average person ‘switching’ from voting left to voting right by around 0.5–1%. We also have evidence that winning more in the National Lottery increases the probability of an average person being less egalitarian by agreeing that “ordinary people already get a fair share of the nation’s wealth” and therefore there is no need for a redistributive policy.

This study is designed as a small step on the path towards a causal understanding of people’s voting choices. Currently, the reasons for individuals’ attitudes to politics and redistribution are not fully known. This paper has suggested a complementary way to explore one important aspect of the issue. It has examined longitudinal data on lottery winners in Great Britain. By comparing people before and after a lottery windfall, it has found evidence that winners tend to switch to support for a right-wing political party, and to be less egalitarian. Importantly, the finding is also of a ‘dose-response’ kind: the larger the win, the more people tilt to the right. Small wins have no significant consequences.

Our results are consistent with the view that individuals’ political beliefs are shaped in part by self-interest. They appear to be valuably complementary to a set of modern experimental findings that have emerged from the laboratory.

Finally, our study provides an important implication for the understanding of people’s attitudes towards inequality and deservingness of wealth. A belief typically held by individuals who are anti-redistributive policies is that the rich “earned” their keep whereas the poor did not, hence providing the reason why there is no need for the rich to redistribute their incomes to the poor. Yet the current study shows that people’s attitudes towards inegalitarian can change significantly following an increase in incomes that are not even earned through efforts. What this implies is that our feelings of deservingness are often easily rationalized even when we do not have an appropriate base (e.g. efforts) for it.

Powdthavee, N, A.J Oswald (2016): “Does money make people right-wing and inegalitarian? A longitudinal study of lottery winners,” PIER Discussion Paper, No.16.