Friends or Foes: Foreign Flows in the Thai Government Bond Market

excerpt

Over the past decade, foreign participation in emerging market economies (EMEs)’ sovereign bond markets has increased markedly. This raises questions about the transmission of global shocks into EMEs. This article presents some empirical findings that, in the case of Thailand, foreign activity is indeed significantly associated with the observed yield movements. Whether this is a cause for concern, however, would really depend on the deep underlying source of such influence, which this article also attempts to uncover.

Local currency sovereign bond markets in EMEs have grown substantially in the past two decades. For many Asian EMEs including Thailand, this was a direct outcome of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, which not only put many governments in difficult fiscal positions, but also drove home the need for a more diversified financial system. Among other reforms, the development of a deep and liquid local currency bond market was seen as a solution to both of these problems.

Increased foreign participation in EMEs’ local currency bond markets was a relatively more recent development. In fact, as late as in the early 2000s, there was still a strong conviction in the academic community that for most countries obtaining external funding through the domestic local currency bond market would be met with little success. Most vocal of this “original sin hypothesis” were Eichengreen, Hausmann, and Panizza (1999, 2002), who asserted that because of such factors as transaction costs, network externalities, and market imperfections, most (smaller) economies lacked the capacity to borrow abroad in their own currency.

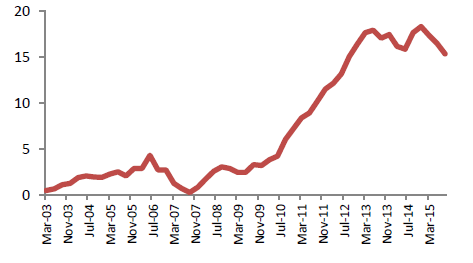

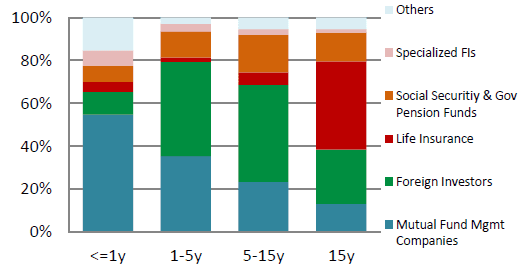

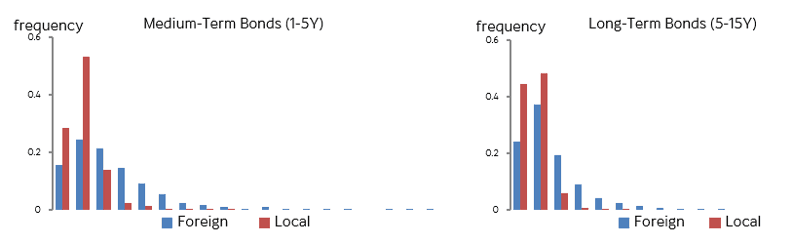

But as the EMEs’ local currency bond markets continue to deepen and as monetary policy in major economies become increasingly more accommodative, it has become clear that at least this particular version of “original sin” is a condition countries can lift themselves from. As can be seen in Figure 1, foreign holdings of Thai government bonds have increased remarkably, especially after the 2008–09 global financial crisis. In terms of trading activity, foreign investors have also come to play a very active role. As seen in Figure 2, which shows market participants’ share of trading volume in different segments of the Thai government bond market, foreign activity constitutes as much as 40% of the total volume for the medium- and long-term segments.

Perhaps a bit of both…

Surely, foreign participation in the domestic local currency bond market does bring with it a number of benefits to the recipient economies.1 For one, it certainly broadens the pool of funds that domestic borrowers – whether they be the government or the private sector – can obtain beyond those locally available. An added benefit is that, compared to other external financing options, these funds can be obtained at rates that are (reasonably) domestically determined and without any resulting currency mismatch (given the local-currency nature of the market). Further, insofar as foreign investors bring with them contrarian views to domestic players, their presence can be beneficial in moderating market price movements. And in markets where local investors may not be as sophisticated or active, foreign activity can also aid the market’s price discovery process, since such activity can reveal important information about the fundamentally justified price that the bonds should be traded at.

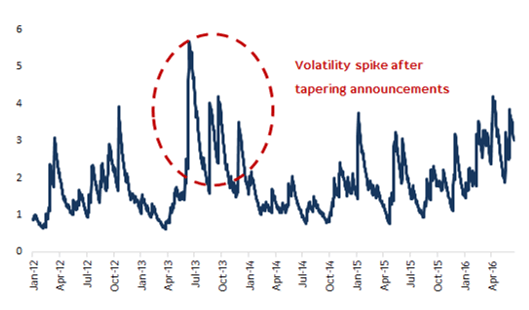

Yet undeniably, substantial foreign participation also poses potential challenges. For one, increased foreign participation can be associated with sharp asset price movements, not only in the bond market but also in the currency market, especially during unstable periods. A recent example of such a period is the 2013 taper tantrum episode, where the Federal Reserve’s announcement to scale down its asset purchasing program led to increased volatility in a number of EMEs’ bond markets, including Thailand’s (Figure 3). Part of this spillover may have to do with the fact that foreign investors have become such important players in these markets, so their reactions (and trading actions) to such news were definitely bound to have important implications for market yields.

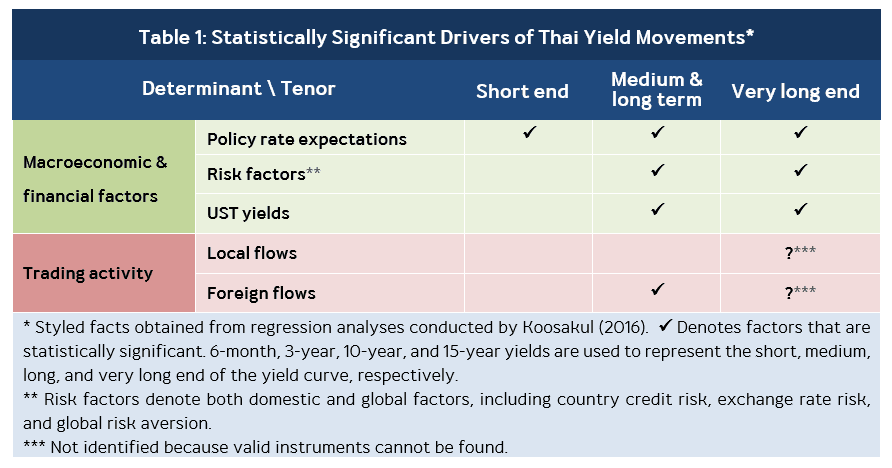

To find the drivers of yield movements in the different segments of the Thai yield curve, Koosakul (2016) conducts regression analyses on a number of macroeconomic and market factors (Table 1 below). The paper finds that at the short-end of the yield curve, domestic factors, namely policy rate expectations and bond supply, are the main factors behind the observed movements. By contrast, longer-tenor yields are also found to be affected by global factors, namely global monetary conditions and global risk appetite.

But the set of results that is perhaps more related to the present discussion is the paper’s finding that the trading activity of foreign players, and not that of local players, is also responsible for the observed yield movements in the Thai market, at least in the medium- and long-term segments where foreign entities are significant market players. Coupled with the finding that Thai bond yields are significantly linked to global monetary conditions and global risk appetite, this result lends further support to the idea that the Thai bond market’s condition is indeed materially exposed to developments at the global level.

But why, exactly, does foreign activity have an impact on Thai yield movements while local activity does not? And is the detected foreign influence all that alarming?

From a market microstructure perspective, there are at least two explanations for why the trading activity of certain market participants may affect asset price more than others’. The first explanation, which is related to asymmetric information, revolves around the idea that certain market participants may possess better (or “private”) information about the fundamental value of the particular asset than others. In light of this informational asymmetry, whenever there is significant aggregate buying or selling pressure (the so-called “order-flow”) from these participants, market makers may choose to adjust their quotes in an attempt to mitigate potential adverse selection costs. In the Thai context, it could be the case that foreign players are perceived as better informed about external developments, which are also found to significantly influence the medium- and long-tenors of Thai yields, than local players. Alternatively, it is also possible that local and foreign players have access to the same set of information, but through better analytical and technical ability the latter are better able to deduce what this public information implies about the current and future values of Thai yields.

Another potential market microstructure explanation for the detected foreign influence is inventory risk control. Under this theory, whenever (risk-averse) dealers provide liquidity to their customers, they do so with a premium to compensate for the undesired inventory risk that materializes from the trades. Applying this explanation to the Thai case, it is possible that foreign flows are substantially larger in magnitude than local flows, and hence the former have a greater impact on bond yields because inventory risk-concerned dealers would have to more actively adjust their quotes when dealing with the former than the latter.

An examination of the Thai Bond Market Association (ThaiBMA)’s dataset indicates that the size of foreign flows is indeed a lot larger than domestics flows (Figure 4). Nevertheless, after conducting further statistical analyses, Koosakul (2016) finds stronger evidence in favor of the information explanation than the liquidity explanation. This led the author to conclude that foreign players lead yield movements in the Thai context not because of the sheer size of their transactions, but because they are (or, at least, perceived to be) better informed than local players.

Now, this finding has direct implications for whether the detected foreign influence should be viewed as a cause of concern. Specifically, if the influence of foreign flows is due purely to the liquidity effect, then perhaps one is right to express some concern. This is because, through sheer size, foreign flows can cause Thai bond yields to deviate significantly away from the fundamentally justified levels. This can have implications for monetary policy, since the resulting yield movements may not necessarily be consistent with the domestic central bank’s monetary policy stance. It can also have financial stability consequences, if the (potentially abrupt) yield adjustments cause important financial players to sustain large trading losses. Abrupt foreign actions can also cause other market participants to “panic trade”, which may propagate the initial shock even further.

On the other hand, if the detected foreign influence is due to informational reasons, which appears to be the case for Thailand, then the situation may not be so grim. This is because in this case the detected influence could simply be a reflection that foreign activity has proved useful to Thai dealers in providing price-relevant, otherwise dispersed, information about the yields Thai bonds should be trading at. In other words, Thai dealers may have partly been relying on observing foreign activity as a means to arrive at the fundamentally justified yields that they should quote to their customers. It is based on this reasoning that Koosakul (2016) concludes that foreign flows may actually have been beneficial forces to the Thai market’s price discovery process, and therefore could be considered more as its friends than foes.

But the above story is not the only one consistent with the observed results. It could very well be that foreign activity does not provide fundamentally consistent information, but it is thought to do so all the same. In this case, foreign flows could still be driving Thai yields away from the levels justified by fundamentals, much like they would under the liquidity paradigm.

In any event, a market that relies heavily on a particular group of participants – foreign investors in this case – to aid price discovery is not one that is resilient to idiosyncratic shocks that may cause these participants to behave irrationally in certain circumstances, regardless of whether these players provide fundamentally relevant information in most situations. In this light, the long-term solution suggested by Koosakul (2016) is to promote the level of activeness/sophistication of local investors, so as to lessen the degree of informational asymmetry in the market.2 This way, the Thai bond market can enjoy the full benefit of foreign participation with minimal risk of disruption during an unexpected turn of events.

Foreign flows into EMEs have increased significantly in the past two decades. This article provides a brief general discussion on the benefits and challenges that such a development presents to the recipient markets. For the Thai case, it appears that foreign presence does bring with it a benefit above and beyond the ability of the Thai government to obtain long-term external funding in local currency. In particular, there appears to be some (albeit preliminary) evidence that foreign activity may actually have been beneficial to the market’s price discovery process. Nevertheless, efforts should still be put in to lessen the degree of information asymmetry in the market, so that the Thai government bond market can enjoy the full benefit of increased foreign participation with minimal risk to economic and financial stability.

Eichengreen, B., and R. Hausmann (1999), “Exchange Rates and Financial Fragility”, In New Challenges for Monetary Policy. Proceedings of a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Eichengreen, B., R. Hausmann and U. Panizza (2002), “Original Sin: The Pain, the Mystery and the Road to Redemption”, paper presented at a conference on Currency and Maturity Matchmaking: Redeeming Debt from Original Sin, Inter-American Development Bank.

Khanthavit, A. (2015), “The Components of Bid-Ask Spread in Thailand’s Government Bond Market”, Chulalongkorn Business Review, 37, 146, 58–75.

Koosakul, J. (2016), “Daily Movements in the Thai Yield Curve: Fundamental and non-Fundamental Drivers”, PIER Discussion Paper no. 30/2016.

Peiris, S. J. (2010), “Foreign Participation in Emerging Markets’ Local Currency Bond Market”, IMF Working Paper, 10/88.

The opinions expressed in this discussion paper are those of the author(s) and should not be attributed to the Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research.

- For a more detailed discussion of the benefits and costs of foreign participation, see, for instance, Peiris (2010).↩

- In a way, the uncovering of informational friction in the Thai government bond market, as well as the ensuing policy recommendation, in this article is similar to the finding and suggestion by Khanthavit (2015). The only difference is that, because of difference in research methodologies, Khanthavit (2015) identifies a subset of local investors as informed investors in the Thai government bond market, whereas this article finds that foreigners are the informed investors.↩