Fiscal Space in Open Economies

excerpt

Debt/GDP and other measures of debt burden have risen substantially during and after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009. Yet, not all debt overhangs are equal. The purpose of this analysis is to study the heterogeneity of economic outcomes driven by fiscal space in the advanced economies as well as emerging market and developing economies of recent decades, and to identify factors influencing the prospect of a country for a given fiscal space. We compare and rank countries’ fiscal space, and look at economic structure to investigate the degree to which economic growth is sensitive to these variables.

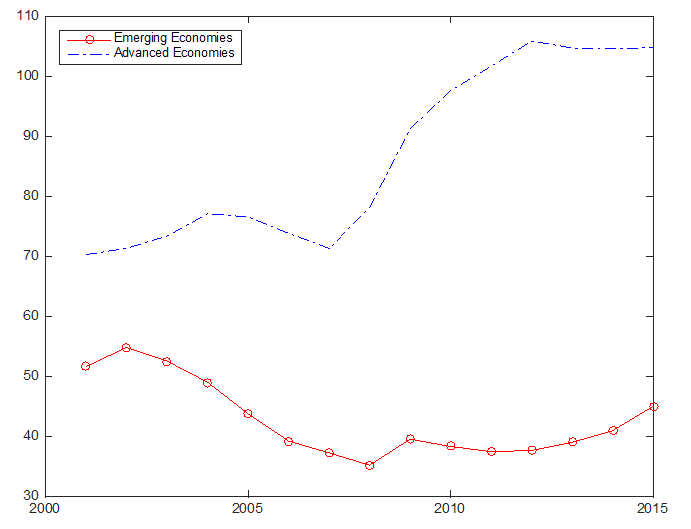

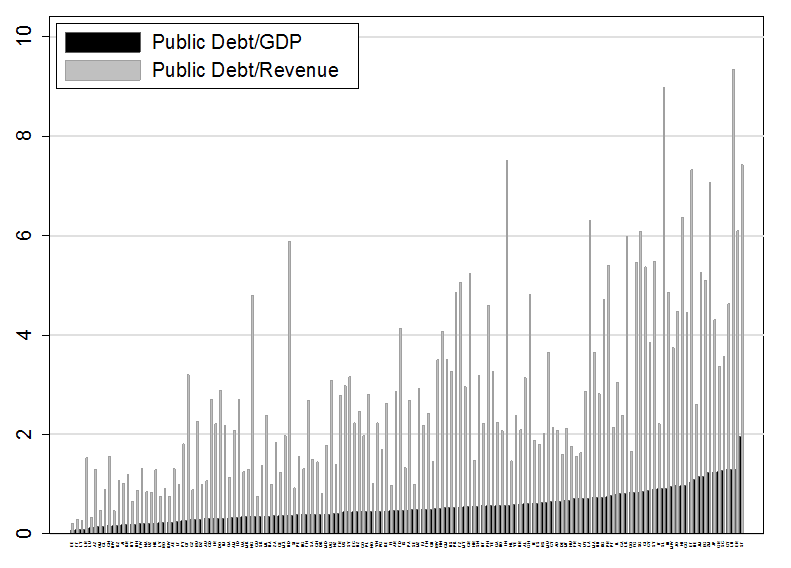

Figure 1 shows the level of public debt/GDP from 2001 to 2015. Public debt here is drawn from the World Economic Outlook database, which reports the general government gross debts of IMF member countries. What would happen if and when the global interest rate increases, say by 1% or 2%, to countries with large public debt, small tax base, and limited fiscal space? Will they face a massive shock, as the present close to zero interest rate allows the illusive feeling of happy go lucky? To answer this important question, it turns out that more understanding on the cross-country patterns of fiscal space and the association with other macro variables is necessary.

Fiscal policy is predicated on fiscal space and fiscal capacities. While there is no consensus on the operational definition of fiscal space, the notion deals with the degree to which a country has the capacity to finance its budget without a sizable increase in the real interest rate. Heller (2005) defines fiscal space broadly as room in a government´s budget that allows it to provide resources for a desired purpose without jeopardizing the sustainability of its financial position or the stability of the economy. Ostry et al. (2010) identify fiscal space as the difference between the current level of public debt and the debt limit implied by the country’s historical record of fiscal adjustment. Auerbach (2011) uses the notion of fiscal gap: the immediate and permanent tax increase or spending cut (or combination) that would keep the debt/GDP ratio at the same level in the long term as it is now.

In this analysis, we consider easy-to-track ratios of fiscal space: fiscal balance/GDP, public debt/GDP, fiscal balance/revenue, and public debt/revenue. The first two have been frequently used by the literature and policy makers as the key indicators for soundness of fiscal positions and readiness for exposure to confidence crises. For instance, the Maastricht criteria imposed thresholds of public debt/GDP below 60%, and fiscal deficit/GDP below 3% as criteria for joining the Euro. The last two measures provide alternatives for comparing fiscal space across countries and time by normalizing public debt and fiscal balance by government revenue. A given ratio of public debt/GDP, say 66.5% of Brazil, is about twice that of New Zealand, 35.0%. Accounting for government revenue, more specifically tax/GDP, which is 36.0% for Brazil and 32.1% for New Zealand, Brazil’s public debt/tax is also twice that of New Zealand. In this example, public debt/GDP gives consistent estimate of fiscal space to public debt/tax. Consider now Thailand: public debt/GDP is 46.1%, while tax/GDP is 19.1%, resulting in public debt/tax of 2.4, a higher ratio than that of Brazil, but lower than 2.7 of the U.K. (public debt/GDP of 89.2% and tax/GDP of 32.6%). Comparing public debt/GDP and public debt/tax thus provides a mixed view of an otherwise reasonable matrix associating with fiscal space across countries.

Subject to data availability of tax collection across countries and time, we use budget revenue/GDP, averaged to smooth for business cycle fluctuations, to provide key information on the revenue base to support fiscal policy. Essentially, the public debt/GDP normalized by the revenue measures the average revenue years that it would take to buy the outstanding public debt, and provide a stock measure of public debt overhang. The interpretation of this fiscal space measure depends on the assumption that revenue base is subject to structural factors that are harder to modify in the short run than adjusting government expenditure. The evidence supports that changing taxes tend to be difficult in polarized countries and income inequality is negatively associated with the size of tax base/GDP (Aizenman and Jinjarak, 2011). Globalization has induced countries to embrace greater trade and financial integration, in the process shifting their tax revenue from easy-to-collect taxes (tariffs and seigniorage) towards hard-to-collect taxes (VAT and income taxes) (Aizenman and Jinjarak, 2009). The usefulness of de facto fiscal space measures also extend to explaining sovereign risks across countries than the more conventional public debt/GDP (Aizenman, Hutchison, and Jinjarak, 2013).

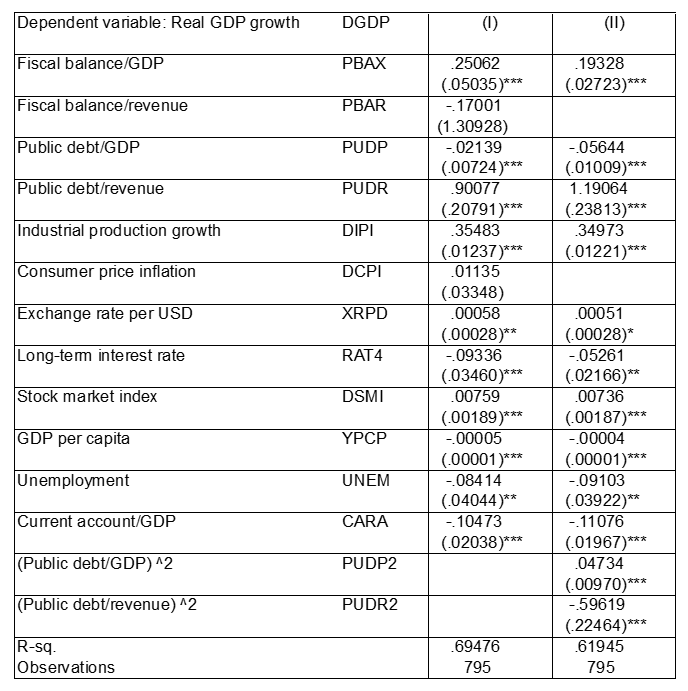

Instead of depending on any specific measure of fiscal space, we provide here a horse race of variables on their explanatory power. The data are drawn from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), covering 1980–2015 (estimation sample 1982–2015) and 201 countries (estimation sample 54).1 The dependent variable of interest is Real GDP Growth (%). Fiscal space measures are Fiscal Balance/GDP (%; PBAX), Fiscal Balance/Revenue (PBAR), Public Debt/GDP (%; PUDP), and Public Debt/Revenue (PUDR). Control measures include Industrial Production Growth (%; DIPI), Consumer Price Inflation (%; DCPI), Exchange Rate per USD (XRPD), Long-Term Bond Yield (%; RAT4), Stock Market Appreciation (%; DSMI), GDP per Capita ($ PPP; YPCP), Unemployment (%; UNEM), Current Account/GDP (%, CARA).

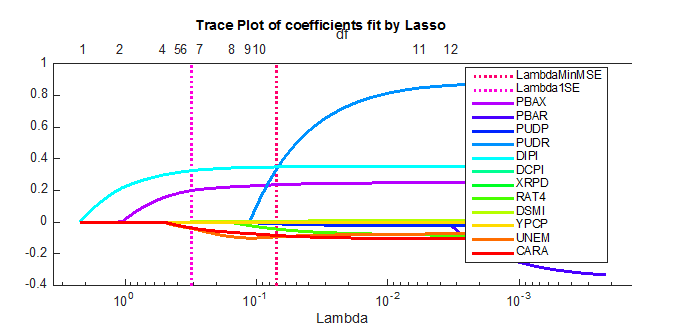

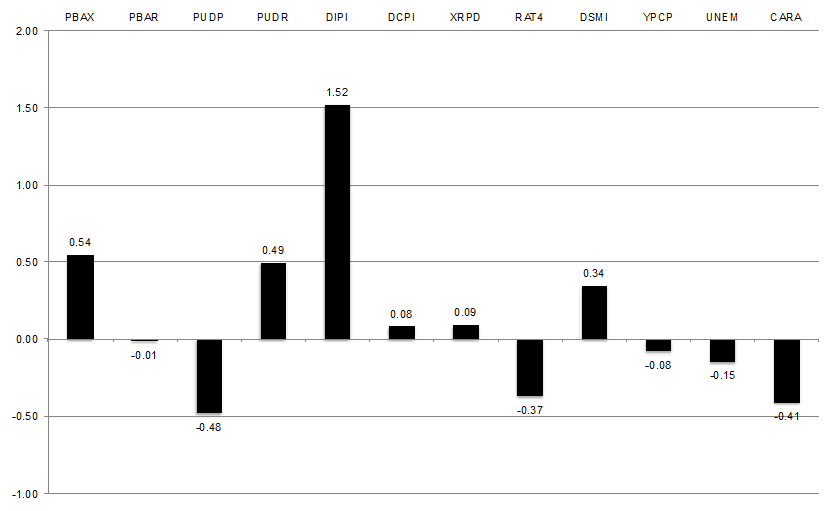

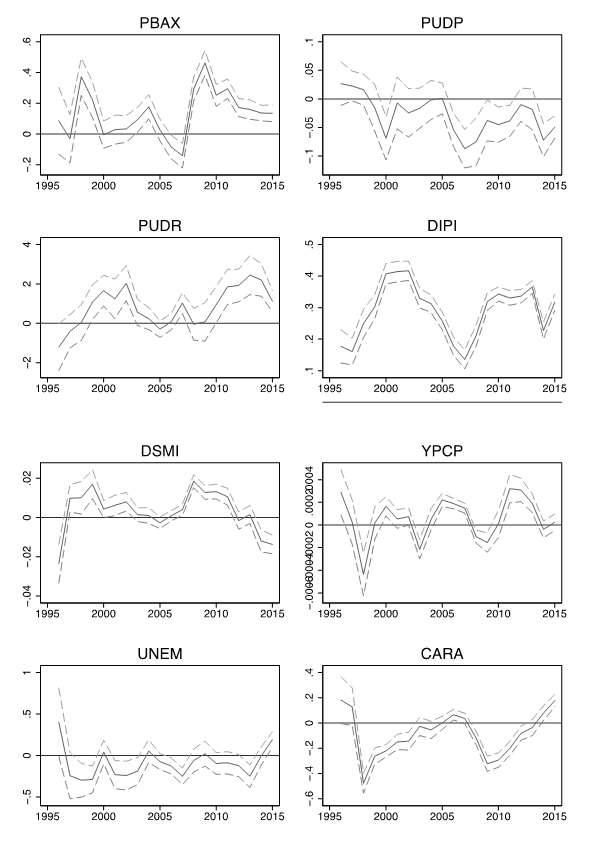

Using the data of past three decades, Figure 2 plots the ratios of average Public Debt/GDP and average Public Debt/Revenue. While the association between the two variables is generally positive, the statistical correlation is 0.7. Figure 3 provides trace plot of coefficients fit by Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO). Of the twelve explanatory variables, the four most statistically significant are Industrial Production Growth, Fiscal Balance/GDP, Current Account/GDP, and Unemployment (Figure 3). To provide a sense of economic significance across the variables, we calculate the products of one standard deviation change of each variable and the variable’s coefficient estimate from the fixed-effects panel estimation (reported in Appendix Table 1, column I). Shown in Figure 4, the most economically significance variable is Industrial Production Growth (a one standard deviation increase results in 1.52 percent increase in GDP growth), followed by Fiscal Balance/GDP (0.54%), Public Debt/Revenue (0.49%), and Public Debt/GDP (-0.48%). Overall, fiscal space measures explain approximately 12 percent of variation in the growth data (Appendix Table A1, column II). Using rolling regressions, we also find that the importance of each variable is varying over the years (Appendix Figure A1).

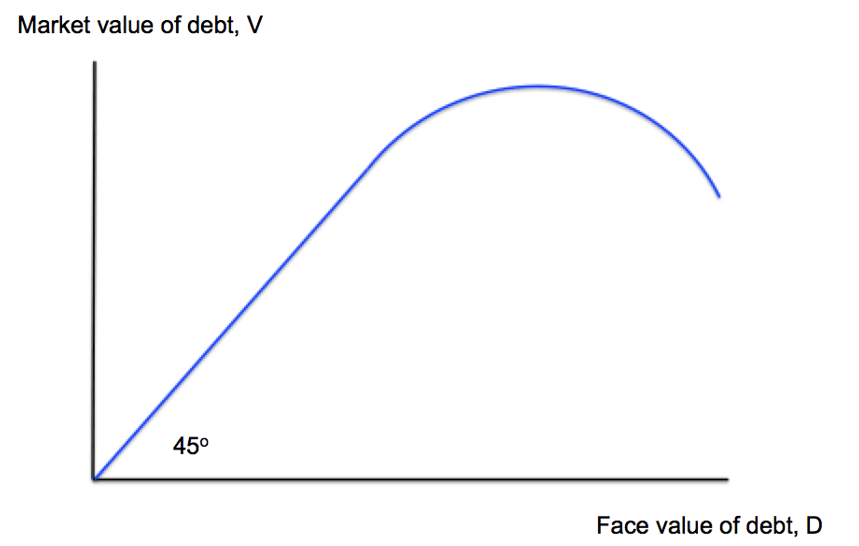

How can we explain the negative association of Public Debt/GDP and positive association of Public Debt/Revenue on economic growth? Figure 5 depicts the debt laffer curve. To understand the effects of limited fiscal space on economic performance, it is useful to recognize the causality between debt problems and growth is bidirectional. A legacy of debt generates the effective creditor’s tax on debtor’s investment and thus economic growth. There is already a large number of studies on the relationship between economic growth and public debt/GDP. By and large, the findings suggest a negative relationship between public debt/GDP and long-run growth, but no evidence for a similar debt threshold within countries (Eberhardt and Presbitero, 2015). Intriguingly, in a horse-race of variables we find the opposite effects of Public Debt/GDP and Public Debt/Revenue, both their linear and polynomial terms (reported in Appendix Table A1). Our evidence seem to point to non-linearity and the accounting for government revenue in assessment of whether a country is on the wrong side of debt laffer curve.

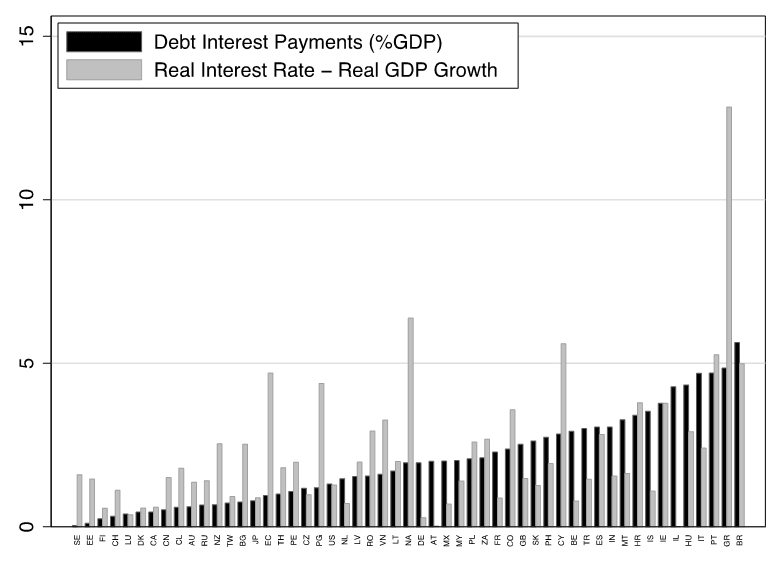

What else can we learn from fiscal space? Clearly, there is a need to systematically compare different, above-mentioned measures of fiscal space and fiscal gaps. Then, allowing more explicitly backward looking and forward-looking factors and exploring interactions between revenue, expenditure, and debt can be effectively evaluated.2 In addition, we have so far abstracted from monetary policy, yet studying jointly budgetary issue and effectiveness of monetary policy, as well as fiscal dominance (i.e. if and when the cost of servicing debts has become so high that interest rates have to be set to keep it manageable rather than to controlling inflation; see Figure 6), together with deriving fiscal policy response subject to fiscal space in varying global economic scenarios should be a useful exercise.

It is likely that the global financial crisis has already rearranged the economic relationships between fiscal space and economic institutions, as well as the interdependence of fiscal elements among countries, thereby invalidating some of the empirical findings here. While such rearrangement will influence the path of adjustment for public debt, economic growth, and institutions, we have identified several factors determining the fiscal space and the heterogeneity of economic performance driven by it. Needless to say, more data and country-case studies should shed new light on the economic significance of fiscal space in the open economies. It is not clear how one could play down the importance of fiscal capacity and fiscal solvency, be it in the advanced economies or emerging markets. To quote Ernest Hemingway: “How did you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

Aizenman, J., M. Hutchison, and Y. Jinjarak (2013): “What is the Risk of European Sovereign Debt Defaults? Fiscal space, CDS Spreads and Market Pricing of Risk,” vol. 34, pp. 37–59.

Aizenman, J. and Y. Jinjarak (2009): “Globalisation and Developing Countries – A Shrinking Tax Base?” Journal of Development Studies, vol. 45, pp. 653–671.

Aizenman, J. and Y. Jinjarak (2011) “The Fiscal Stimulus of 2009–2010: Trade Openness, Fiscal Space, and Exchange Rate Adjustment,” NBER International Seminar in Macroeconomics, pp. 301–342.

Aizenman, J. and Y. Jinjarak (2012): “Income Inequality, Tax Base and Sovereign Spreads,” FinanzArchiv, vol. 68, pp. 431–444.

Auerbach, A. J. (2011): “Long-term Fiscal Sustainability in Major Economies,” BIS Working Papers No 361.

Chucherd, T., S. Angklomkliew, and P. Apaitan (2016): “The Perspectives of Debt Dynamic and Fiscal Limit on Fiscal Sustainability in Thailand,” Thammasat Economic Journal, vol. 34, pp. 57–105.

Eberhardt, M. and A. F. Presbitero (2015): “Public Debt and Growth: Heterogeneity and Non-linearity,” Journal of International Economics, vo. 97, pp. 45–58.

Heller, P. (2005): “Back to Basics – Fiscal Space: What It is and How to Get It,” Finance & Development, vol. 42, no. 2.

Ostry, J., A.R. Ghosh, J.I. Kim, and M. Qureshi (2010): “Fiscal Space,” IMF Staff Position Note SPN/10/11.

- The final sample includes 54 countries from 1982–2015: AT, AU, BE, BG, BR, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IL, IS, IT, JP, KR, KZ, LT, LU, LV, MX, MY, NL, NO, NZ, PE, PH, PL, PT, RO, RU, SE, SI, SK, TH, TN, TR, TW, US, VN, ZA. See ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 codes definition.↩

- See for example Chucherd et al. (2016) for the case of fiscal mismatch confronting Thailand in the presence of aging society, potentially causing a significant increase in public debt/GDP, the scenario likely applicable to many middle and upper-income countries.↩