Thailand’s Pension Reform: Towards an Inclusive, Adequate and Sustainable Pension System

Schedule

| 8:30 | Registration | ||||||||||

| 9:00 | Welcoming Remark by | ||||||||||

Opening Remark by | |||||||||||

Setting up the context Moderator: จินางค์กูร โรจนนันต์ (สำนักงานสภาพัฒนาการเศรษฐกิจและสังคมแห่งชาติ)

| |||||||||||

| 10:15 | Break | ||||||||||

Ideas on how to reform the pension system in Thailand Moderator: Titanun Mallikamas (Bank of Thailand)

| |||||||||||

| 12:00 | Lunch break | ||||||||||

| 13:30 | Round Table: The Future of the Pension System Moderator | ||||||||||

| 15:00 | Break | ||||||||||

| 15:15 | Wrap-up and summary of the key discussions by | ||||||||||

| 15:45 | Closing Remark by | ||||||||||

Summary

Thailand is aging extremely fast. The share of the population aged 60 years or over is projected to increase from 19% in 2020 to 39% in 2040, due to a combination of increasing life expectancy and low birth rates. It is one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world.

While Thailand has multiple social insurance and social assistance schemes to support the elderly, the old-age income provided by these schemes is inadequate for many groups of population.

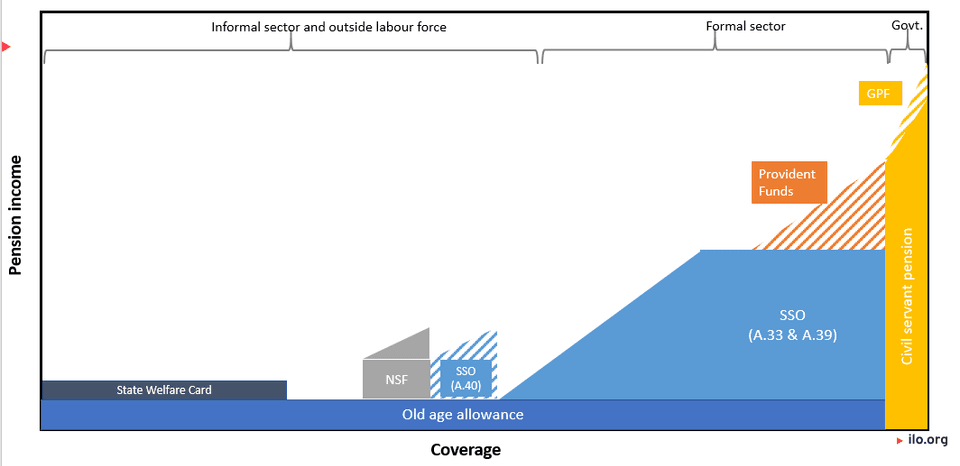

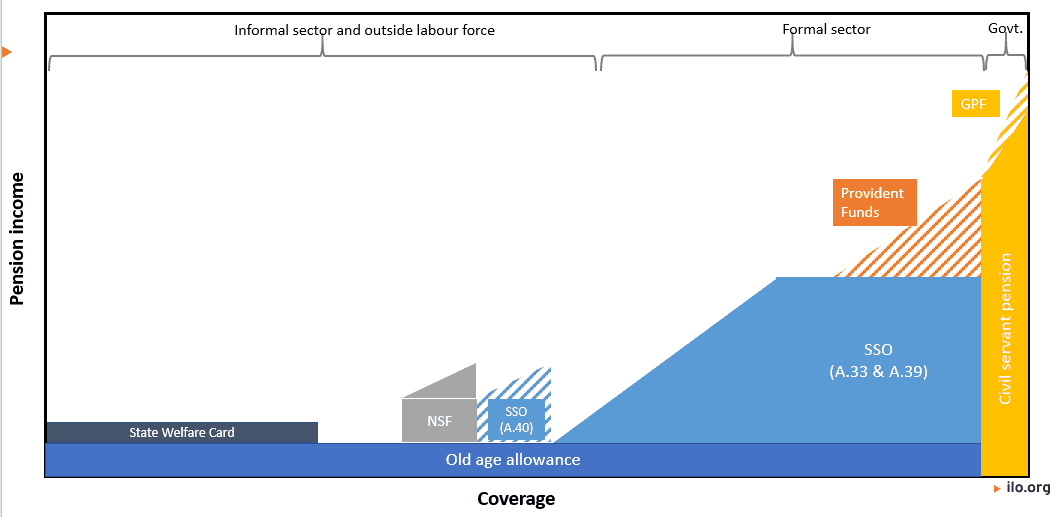

Figure 1 illustrates the current old-age income support system in Thailand. The different schemes are in theory targeted at different groups or sectors of the population. The Old Age Allowance (OAA) provides a basic pension for all Thai citizens aged 60 years or older except retired civil servants, who have their own government pension schemes. The Social Security Office (SSO) Fund is mandated for employees in the formal sector (Article 33). Once exiting the formal sector, an employee can choose whether to continue to contribute to the fund (Article 39) but with a lower accrual of benefits. Those in the informal sector can choose to participate in the voluntary schemes either the SSO Article 40 or National Savings Fund (NSF).

The current generation of Thai elderly often rely on their children for support. However, with longer life expectancy, lower fertility and the shift towards smaller families, it will be more difficult for the future generations to count on their children. Public old-age income support is expected to play a more important role.

There have been several proposals on how to combat the old-age income problems from different parties – experts, government agencies, parliament members and a group of citizens. For example, a group of parliament members proposed a bill to increase the OAA to the poverty line. The Ministry of Finance proposed setting up the mandatory provident fund for formal sector employees.

The forum brought together experts in the field to discuss and share their ideas on how to reform the old-age income systems in Thailand.

The three groups of experts (Wasi et al. 2021, ILO, World Bank) share several common views, with differences in details.

First, to solve the old-age income problem, the focus should be put on designing the whole old-age income support system, not on any individual scheme. Thai elderly can receive income from many sources (schemes) and what needs to be considered is whether their total income is adequate. Currently, Thailand’s public old-age income support schemes are fragmented and managed by different governmental authorities with little integration and a lack of policy consistency. The responsible agencies often think about reforming their own scheme without a clear vision on how their adjustments will affect the fiscal space of other schemes.

Second, it is urgent to have an integrated vision and framework for old-age income policies in Thailand and a national committee could be strategic for this objective. This is to ensure that the contributory, non-contributory, and voluntary savings schemes complement each other and contribute to the same goals. Altogether the goals are to make pension income adequate, insure against longevity risk for all Thai elderly and to ensure that all schemes are financially sustainable. The horizontal, vertical, and intergenerational redistribution can be done by harmonizing direct and indirect redistributive tools. Such a big reform may require a political buy-in and support from every level. Ad hoc measures, such as launching new schemes (e.g. the proposed National Pension Fund), should be postponed and any proposal for reform should be assessed taking into consideration the overall vision and framework.

Third, for all old-age income support schemes, indexation is needed. No indexation means the specified amount of pension benefits, wage ceilings and past earnings will have lower value over time and not respond to their objectives at the time of its initial definition. All of these elements should be flexibly indexed to inflation or wage growth (or a combination of those). The SSO wage ceiling has been capped at 15,000 THB since the fund started. The constant cap implies that the contribution to the fund is capped and the pension benefit for those with monthly income over 15000 is limited and likely inadequate. Keeping the wage ceiling constant means that over time the Social Security will not be able to insure old-age income for its beneficiaries and likely fade away.

Fourth, besides indexation and raising wage ceiling, the SSO mandatory scheme needs parametric reform to make it fairer, more adequate and fiscal sustainable. The ILO has previously assessed that on current scheme rules, there is a high possibility that the funds will be depleted by 2054. To reflect the increase in life expectancy, the retirement age should gradually increase with the possibility of early retirement with an actuarially fair reduction. This will reinforce sustainability and improve adequacy of benefits. To make the scheme fairer, using career average earnings rather than salary of the last 60 working months as the average earnings base may be a solution. Unlike civil servants whose earnings increase over time, some private sector employees have lower earnings toward the end of their careers due to economic conditions or illnesses.

Fifth, the design of old-age pension contributions requires insights in the nature of the country’s labor market. Workers in Thailand have diverse working life histories with many of them moving between formal and informal sectors. Those with short careers in both sectors are likely to be eligible only for lump sum benefits, which will not be adequate to support them throughout the rest of their lives. To accommodate such diverse work histories, a harmonized multi-tiered pension system with portability between public and private system; and strong incentives for voluntary participation is a potential solution.

Lastly, the OAA should be increased although the appropriate level can be discussed. This is essential for the current generation of elderly. For future generations, the OAA does not need to increase uniformly. This can be done by integrating the Social Security mandatory system with OAA, tapered pension system (gradually reducing OAA benefits for those with other pension income), and/or subsidized contribution only for those with low income.

In addition, the ILO and the World Bank view is that reform to the Civil Servants pension needs to be considered. The increasing costs of the scheme – due to generous provision and increasing life expectancy – means that financial sustainability is threatened. A transitioned reform to gradually align the scheme with SSO pension provision will also encourage job mobility and facilitate portability of benefits.